How marine carbon dioxide removal works

The ocean is the largest carbon sink on the planet — it holds almost 50 times more CO₂ than the atmosphere. Marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR) taps into this superpower and leverages the ocean’s natural carbon uptake abilities to maximize how much CO2 it can absorb. Marine carbon dioxide removal, or mCDR, is an umbrella term we use to describe the suite of approaches and technologies that boost the ocean’s carbon uptake.

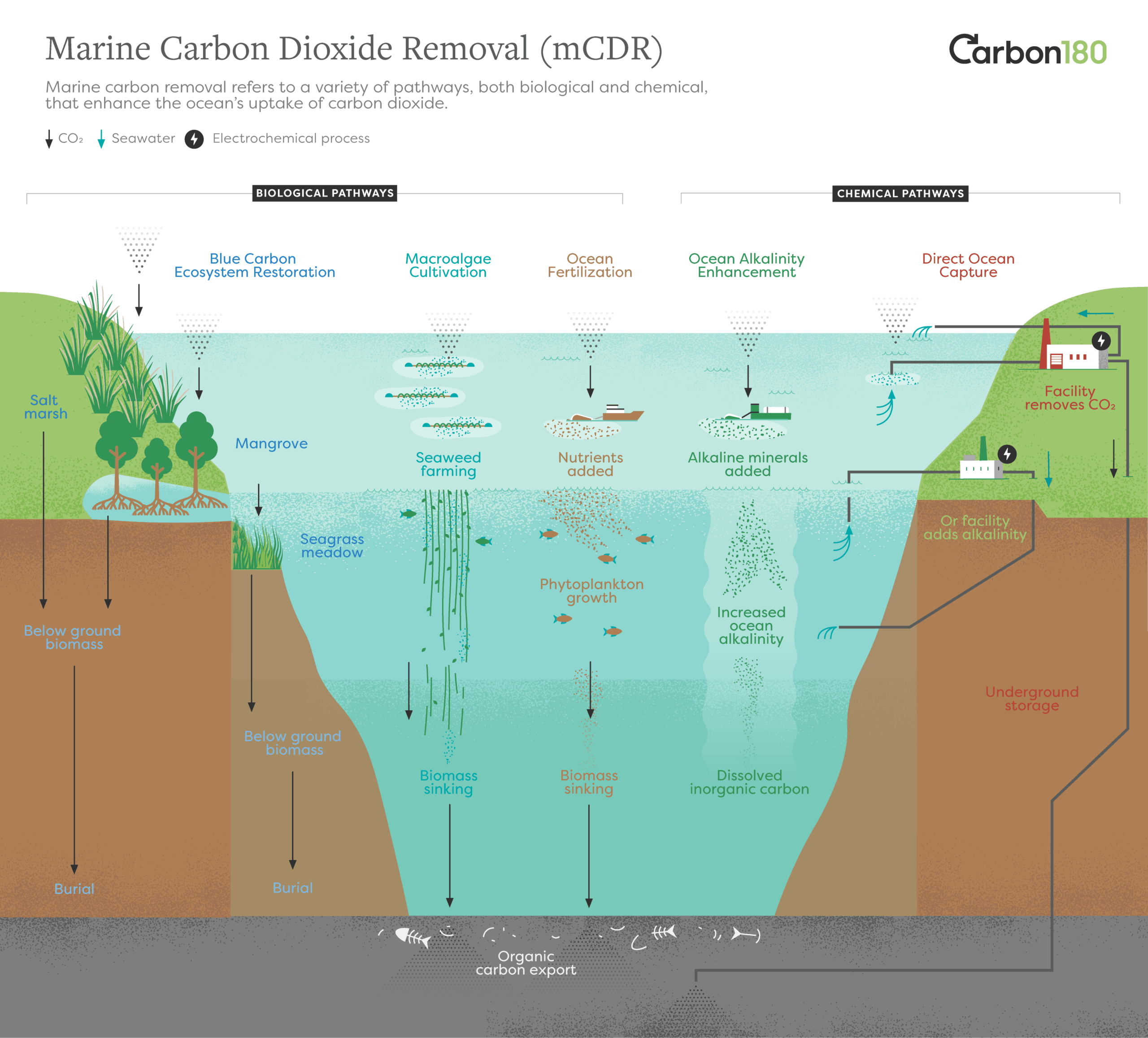

These approaches fall into two broad categories: biotic and abiotic. Biotic (sometimes called biological) pathways rely on ocean life – photosynthesis in the surface ocean by microalgae (phytoplankton) and macroalgae (seaweed, kelp) – to absorb CO2, locking it into their biomass, then exporting that biomass either deeper into the ocean or onto land in the form of durable goods or for long-term storage. Abiotic (sometimes called chemical) pathways rely on the chemistry of seawater – which alone holds over 37,000 gigatons of carbon – increasing the amount of atmospheric CO2 dissolved in seawater and the amount of carbon locked in seawater chemistry where it can stay for thousands of years.

Both types of mCDR pathways involve removing carbon from the surface ocean and storing it for long periods of time, which then allows the ocean to absorb more CO₂ from the atmosphere, and the sheer scale of the ocean’s ability to store carbon makes these pathways exciting to pursue. mCDR holds great promise as a climate solution able to provide safe, scalable, and effective carbon removal – and may ultimately be the most affordable and scalable path to removing gigatons of carbon from the atmosphere.

However, there is still a lot we don’t know about mCDR. Each of these pathways varies in technological readiness, cost, scalability, and environmental and social risks and benefits. The ocean is home to millions of species, and it is a vital source of food and livelihood for many, with 40% of the U.S. population living along the coast. Before any mCDR technique can be deployed at scale, further research, development, and in-water field trials are needed to ensure it can be scaled in a way that is safe, affordable, effective, and just.

We need to be confident in understanding the impact it will have on people and the environment. It’s our job to craft robust policies and advocate for research, development, and governance structures that will only allow the field to advance if it’s done responsibly.

-

Blue Carbon Ecosystem Restoration

The restoration, expansion, and protection of coastal marine ecosystems that have excellent carbon sequestration and storage abilities including mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrasses.

-

Seaweed Farming

Farming of ocean plants such as kelp or seaweeds to increase CO2 uptake in the surface/shallow ocean (or Great Lakes) and conversion to long-term carbon storage via sinking, durable goods, or ocean food-webs.

-

Ocean Fertilization

Increasing the concentration of nutrients (usually iron) in the surface ocean to allow for enhanced phytoplankton growth and carbon export to the deep ocean.

-

Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement

Increasing seawater alkalinity (increasing pH) in order to allow for more CO2 absorption by the surface ocean and conversion to long-term storage as dissolved bicarbonate. This can be done by mineral additions to seawater or beaches, or by electrochemical methods.

-

Direct Ocean Capture

The removal of CO2 directly from seawater via either electrolysis or electrodialysis.

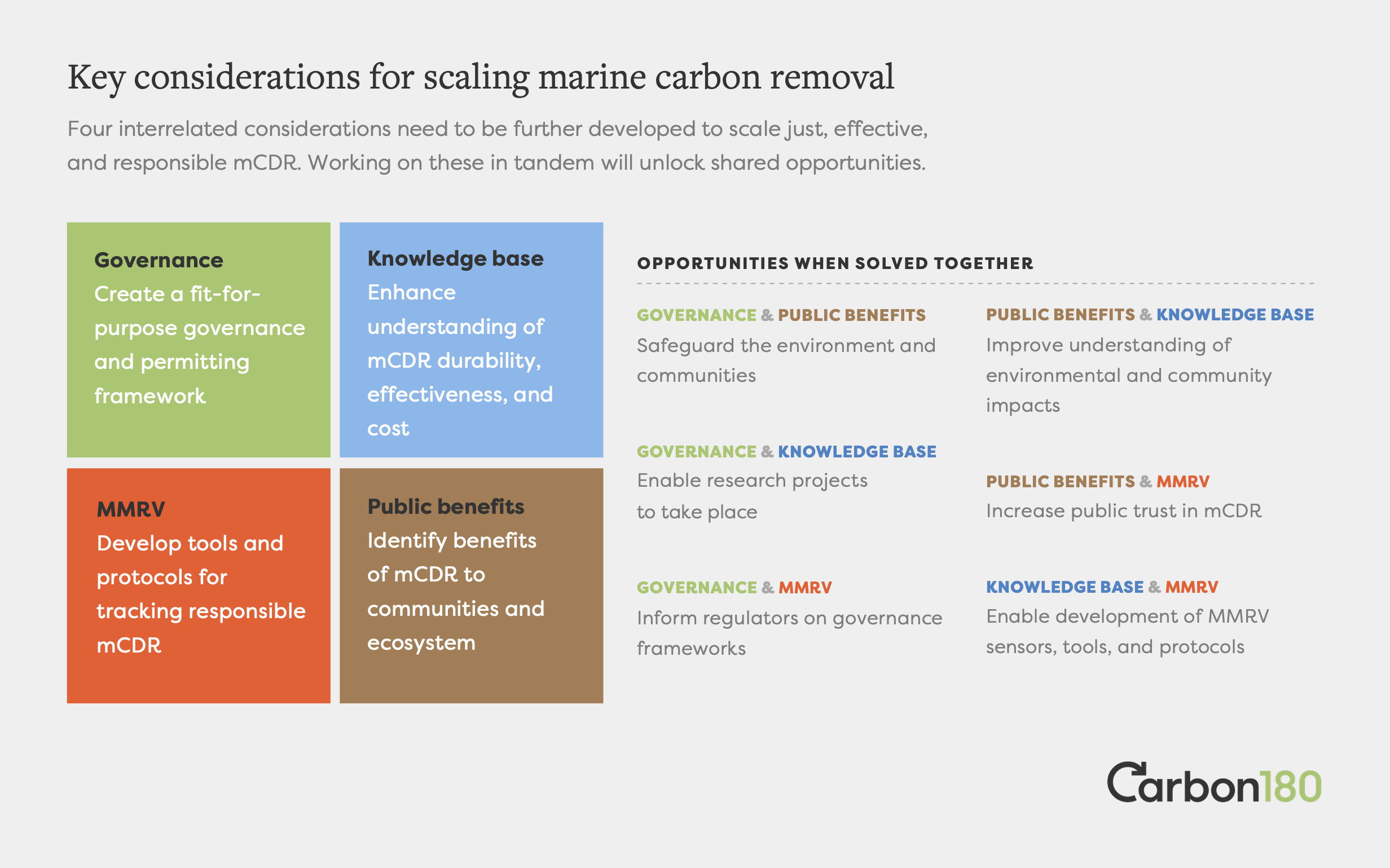

To maximize the benefits of mCDR and grow the field responsibly, four interrelated components must develop side by side. 1) Fit-for-purpose governance 2) Science-backed knowledge base 3) Robust measurement, monitoring, reporting, and verification (also known as MMRV) 4) Identification (and communication) of the environmental and social impacts. Through these four pathways, researchers, communities, and companies will be empowered to make better-informed decisions about their next steps for pursuing mCDR.

Benefits and Opportunities

mCDR offers a range of opportunities for communities beyond climate mitigation. Depending on the approach, mCDR can add environmental and social benefits like ocean de-acidification, job creation, coastal resilience, biodiversity and fisheries boosts, and new economic opportunities for existing sectors. The potential to de-acidify the ocean, in particular, is a rare chance to begin redressing past harms and injustices. Ocean acidification is a direct result of climate change that is impacting important species, hurting vital marine ecosystems, and threatening food security, economies, and culture. The local ocean acidification remediation potential from many mCDR approaches provides an opportunity for ecosystems and communities to recover from this wide-spread consequence of climate change.

mCDR also has the potential to expand the ocean economy and broaden participation in it. The ocean economy is one of the fastest growing, often outpacing the global economy. mCDR can contribute through the integration with existing industries like wastewater treatment, power production, aquaculture, and desalination – and is projected to be a nearly $2.5 billion industry in its own right by 2032. By engaging communities early on in the development of mCDR, coastal communities can be willing and active participants, benefitting from an ocean economy boosted by mCDR.

Marine carbon dioxide removal can play a critical role in curbing climate change, if done responsibly. Through rigorous research and thoughtful policy, we can scale approaches that support climate solutions as well as ocean ecosystems and the communities that depend on them.

Amanda Vieillard, PhDDirector of Policy

Challenges and Considerations

The ocean is vast, complex, and very difficult to observe. Sensors and instruments that can withstand the harsh, salty, cold ocean environment are expensive and difficult to maintain. Fundamental questions remain about both the durability and effectiveness, as well as the potential ecological and social risks of the various mCDR approaches. For example, many of the biotic mCDR pathways carry concerns about ocean deoxygenation (using up all the oxygen in an ocean area) and nutrient robbing (stimulating photosynthesis in the surface ocean could consume nutrients needed elsewhere). We still don’t know the impact of increased alkalinity from abiotic approaches on higher trophic levels like fish, and some types of abiotic mCDR carry a risk of releasing heavy metals into the environment. We need further research to answer these remaining questions in order to ensure only the mCDR approaches that can be proven to be safe and effective can advance. Answering these questions requires investment in research and in the ocean observational infrastructure (sensors, systems, models) needed for mCDR MMRV.

If mCDR is to fulfill its promise to remove CO2 at scale, it must earn trust at the community level. Community-led engagement isn’t a nice-to-have, it’s what is needed to make durable, equitable ocean climate solutions possible. Coastal communities are at the frontline of climate change, with sea level rise, intense and more frequent storms, flooding, and threats to livelihoods based in fishing and tourism. Meaningful engagement with communities can ensure that if and when mCDR grows, communities can benefit, rather than being left behind.

mCDR policy outlook

In an emerging industry like mCDR, federal policy has a major role to play. The first step is to invest in research, particularly in-water testing, that can reduce any uncertainties, identifying mCDR pathways that maximize climate, ecosystem, and community benefits and durably remove CO₂ from the atmosphere. Policy can also support the development of mCDR technologies under a framework of responsible innovation and equitable distribution of benefits. Through early investment into mCDR R&D, the federal government is supporting lab experiments, modeling, field trials, and engaging communities to understand the impacts and effectiveness of various marine carbon dioxide removal strategies.

Federal policy action, therefore, has played a crucial role in catalyzing mCDR research and development, public-private partnerships, and private sector investment. In recognition of the critical role of the ocean in the fight against climate change, the first-ever U.S.Ocean Climate Action Plan sparked investment and activities in ocean-based climate solutions across the federal government. mCDR, as a highlighted priority in the Plan, saw a boom in interest for R&D as a result. In 2023 alone, mCDR saw $36 million from the Department of Energy Sensing Exports of Anthropogenic Carbon through Ocean Observation (SEA-CO2) program, $24.3 million from the National Oceanographic Partnership Program (NOPP, supported by NOAA, DOE, ONR, NSF, and ClimateWorks Foundation), expanded activities within the NOAA Ocean Acidification Program, and new research from NSF. Realizing the potential in mCDR, The White House released the U.S. National Marine Carbon Dioxide Removal Research Strategy to advance safe and effective research on mCDR benefits, risks, and tradeoffs. Additionally, DOE and NOAA signed on to the first interagency mCDR partnership to collaborate on mCDR R&D. EPA also created a pathway for mCDR research projects to apply for permits under the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act (MPRSA), providing a regulatory vehicle for in-water mCDR testing. Agencies such as NOAA, NSF, NASA, ONR, and DOI also have a key role to play in supporting the ocean observing and research infrastructure needed for robust mCDR MMRV. Because mCDR could have far-reaching consequences, good science-backed policies continue to be critically important to safeguarding our ocean’s ecosystems and coastal communities.