Land managers in the United States manage exceptional natural resources in the form of forests, farmlands, and wild spaces, and with those resources come byproducts: seed shells, tree trimmings, corncobs, and more. Often called biomass, this material can become costly when it overloads landfills and burn piles. At a national scale, reports by the Department of Energy and the National Labs suggest that hundreds of millions of tons of biomass could be redirected as a source of carbon for carbon removal. At first glance, it’s a win-win: tackling waste while creating jobs and providing co-benefits.

But for many communities, biomass projects haven’t represented innovation or sustainability. Biomass incinerators and pellet plants, pitched as sustainable solutions, have repeatedly violated pollution standards, harming frontline communities and undermining trust. Bioenergy has redirected farmland from food to fuel production, likely driving global deforestation for new farmland. These traditional models of bioenergy are largely unsustainable but have been incentivized by one-size-fits-all national policies and optimistic claims about biomass sustainability, burdening communities with poorly implemented projects.

What would it take to reenvision biomass usage and realize its benefits while safeguarding against harms? To explore this question, Carbon180, alongside Meridian Institute and World Resources Institute, hosted a listening session with community stakeholders from three regions frequently referenced for their wealth of biomass. We hosted 20 participants from California, the Southeastern US, and the Midwest who shared candid insights on the real-world impacts of biomass projects.

Participants explored the structural changes that would ensure biomass is managed for the needs and well-being of the communities that produce it. Below are some of their insights.

“That’s my community. I live there”

This sentiment underscored a central theme of the discussion: biomass challenges and opportunities are deeply local. While we had grouped participants by region, the challenges facing communities often transcended regional boundaries.

Agricultural communities pointed to practical challenges like high tipping fees for waste hauling, limited access to composting, and the need for a cultural shift as communities increasingly ban open burning of biomass. Rural communities shared the logistical barriers facing remote land managers, and fears that centralized biomass processing would leave them out of a growing bioeconomy. Across regions, participants noted how climate impacts, from wildfires to storms to drought, added unpredictability and urgency to biomass disposal.

Although state and federal policies heavily influence biomass markets, many participants argued that broad financial incentives alone fail to address local needs. Instead of one-size-fits-all incentives, participants advocated for community-driven solutions, such as enabling access to technical assistance and conversion infrastructure. Community cooperatives, they said, should have the resources to develop biomass projects with input on sourcing, co-benefits, and impacts. Additionally, flexible regional infrastructure for processing and converting biomass could ensure benefits extend across agricultural, forest, and urban centers.

Define red lines, not waste

So-called “waste” biomass is often considered sustainable because it consists of remnants from other industries with no inherent economic value. However, participants noted that this definition works better in theory than in practice. They shared stories of overlooked ecological and agricultural benefits, such as refertilized soils or habitat-creating deadwood. They also pointed out that waste rarely has no value; even small economic benefits, like providing cheap firewood or mulch, can be significant locally. Policies based on using “waste” biomass give too broad a license to industry, and fail to account for the ecological and community value these materials may still hold.

Instead, they suggest starting with strict guardrails that protect carbon stocks and biodiversity. This could firmly guide biomass operations towards sources of biomass that need urgent management, such as hurricane windfalls or wildfire cuttings.

It’s all about the scale

Frontline community members warned that as biomass facilities grow larger, so too do the pollution risks and power imbalances, making them increasingly difficult for communities to challenge or control. Larger operations not only concentrate environmental impacts but also reduce local oversight and accountability. In contrast, smaller, community-driven biomass systems offer greater transparency and accountability, making it easier to manage environmental and social impacts. Beyond pollution, large-scale biomass projects often disadvantage small landowners and rural communities because they rely on centralized, high-volume biomass sourcing, which can exclude local producers. Some participants from the Corn Belt did offer a different perspective: in their regions, larger projects can provide stability, helping farmers manage the risks of planting new crops and offering developers protection against the unpredictability of crop failures and rotations.

To address these challenges, participants called for policies that support the growth of smaller, community-led biomass projects. They emphasized the need for investment-risk protections for smallholder farmers testing new crops or rotation systems, insurance mechanisms to buffer against economic uncertainty, and cost-sharing programs for mobile and shared infrastructure that can serve local needs.

Our Next Steps

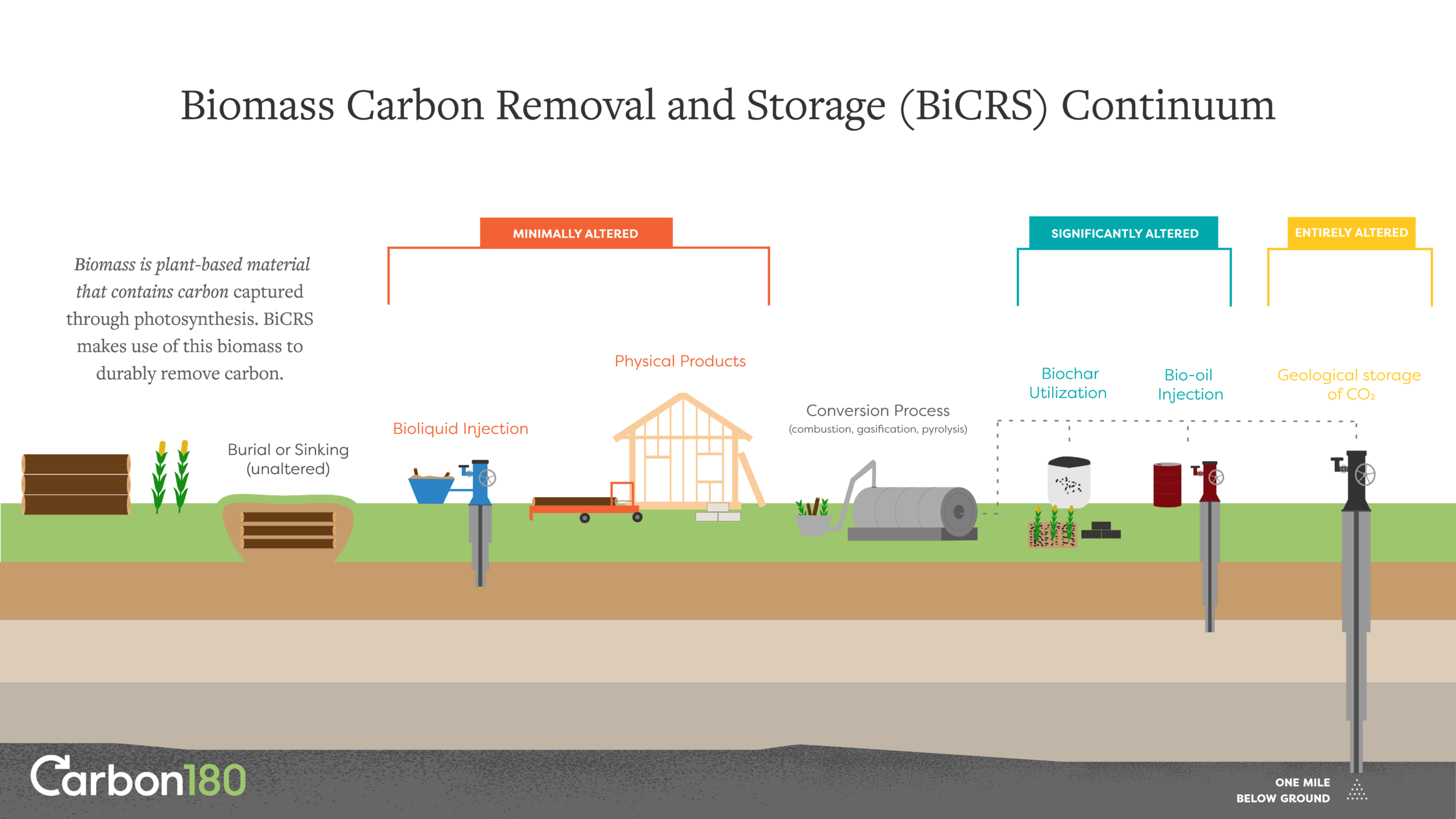

Biomass carbon removal and storage has been embraced by carbon markets, boasting some of the largest investment share to date. Most of these projects are small in size, but bioenergy projects with retrofitted CCS in particular can scale quickly through pre-existing access to capital and technology. However, these same projects are perhaps the worst positioned to provide community benefits and environmental guarantees, due to the centralization of emissions, high volume consumption of select types of biomass, and a poor industry track record of engagement and transparency.

We propose approaching biomass based on the issues it poses for communities, rather than the potential it presents for carbon removal. Communities can be offered a menu of biomass solutions, including non-CDR solutions where appropriate, paired with the capacity and knowledge-building to create locally informed biomass projects. Achieving this will take creativity and curiosity, a critical evaluation of the existing norms of federal and state policy incentives, a reimagining of the optimal scale for successful projects, and new resources to explain innovative approaches like biomass burial. With our partners on the ground, we’re equal to the challenge.